an interview with piero mastroberardino: Campania, pompeii and ancient vines

The Mastroberardino family is a very old and aristocratic family that owns and manages the iconic Mastroberardino winery. Located just 30 miles east of Naples in the small town of Atripalda in the hills of the Campania region, Mastroberardino is one of Italy’s great winemaking estates.

The current president of the estate is Piero Mastroberardino, the tenth generation of the family to run the estate winery. Piero became head of the family estate upon the death of his father, Antonio, early last year. Antonio was one of the leaders of modern winemaking in Italy and was instrumental in preserving the ancient native varieties of the Campania region. For many years the Mastroberardino winery was the only producer of quality Fiano, Greco and Aglianico wines.

Piero shares his father’s passion for these classic wines of Campania. As a poet, artist, scholar and university professor as well as head of a modern winemaking operation Piero combines an innovative vision and a drive for perfection with a deep respect for tradition and his cultural roots.

In 1996, the Italian government selected the Mastroberardino winery to conduct research, plant vineyards and produce wines in the ancient city of Pompeii using ancient varietals and winemaking techniques. Using modern research procedures as well as the writings of ancient Roman historians, Mastroberardino was able to plant native red and white grape varietals in the same exact vineyard locations as their ancient forebears. Mastroberardino successfully produced a red wine using ancient Roman varietals, cultivation and wine-making methods. The first wine to be released was the 2001 vintage and was named Villa dei Misteri after one of Pompeii’s most famous restored sites. Its limited production quickly sold out and it and subsequent releases have become collectors’ items.

Piero was in Washington, D.C. in mid-April to make a presentation on his Pompeii project at a public conference sponsored by Smithsonian Associates and the Scientific Methodologies Applied to Cultural Heritage (SMATCH) organization. Piero graciously agreed to meet with me for an interview prior to his presentation. The following is a lightly-edited transcript of our hour-long conversation.

First, I would like to hear about the derivation of your given name “Mastroberardino.

The origin of the current name dates back to early 18th century. At that time there was a Berardino, who because of his recognized skills as a winemaker was awarded the title “Master” and his descendants were entitled to append the title “Mastro” to the Berardino name, hence Mastroberardino.

This was the beginning of the family name of Mastroberardino which has continued uninterrupted for over two and a half centuries.

Tell me a little about the history of the Mastroberardino winery - when and how it started.

It is the oldest winery in the Campania region. Although the winery actually dates back to the early 1700’s, the date on our wine labels says 1878. That’s when my great-grandfather Angelo officially registered the company as an exporter and he started exporting wines to France and other European markets.

His son, my grandfather Michele, opened the North American markets to our wines. He spent about six months in the U.S., visiting New York and other cities by train, all the while actively promoting our wines.

In the early 1900’s, he made some very long visits by ship to various countries in South America, such as Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. He was very successful in opening these markets to our wines which have remained active markets for us through today. He kept very detailed descriptions of his travels. We actually have documents he wrote that include very detailed observations on the social environment and prevailing political and economic situations of the countries he visited.

countries in South America, such as Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. He was very successful in opening these markets to our wines which have remained active markets for us through today. He kept very detailed descriptions of his travels. We actually have documents he wrote that include very detailed observations on the social environment and prevailing political and economic situations of the countries he visited.

Meanwhile, we continued to add to our vineyard holdings by purchasing some very promising properties in the Irpinia area of Campania.

However, the 1920’s and 30’s were very difficult times for our winery as well as the wine market in general. The first crisis occurred when the financial markets crashed in the late 1920’s. It was a devastating, world-wide recession.

On top of the devastating economic effects of the recession we also had an attack of phylloxera that decimated our vineyards. Adding to our misery was the emergence of the Fascist regime in Italy during the 1930’s and as a result we lost the American and most of the European markets.

And then in the late 1930’s we had the start of World War II which totally disrupted the wine market. The 1940’s were extremely chaotic. We were caught between the Germans, the Americans and our own civil war between the partisans and the Fascists. You couldn’t trust anybody which made it very difficult to produce and sell wine.

The war took a heavy toll on our winery. In addition to all the other problems, the Germans occupied our winery and shot-up our wine barrels as they retreated.

Then my grandfather passed away in 1945 and my father Antonio assumed charge of the winery. It was a very difficult time. Everyone was negative. Economies were decimated, the markets were down and nobody wanted to buy wine.

My father rescued the estate from potential devastation. He took a gamble and replanted the vineyards destroyed by the phylloxera plague with quality, native grape varieties such as Aglianico, Fiano, Piedirosso and Greco di Tufo. This was at a time when many other producers were replanting their vineyards with non-native varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay. He brought quality wines made from native varieties to the market and actively encouraged other producers to do the same. For a long period we were the only winery in the region producing quality wines made from traditional varieties.

It wasn’t until the 1950’s that the markets began to reopen, first in London, which is a very important market, and then elsewhere in Europe and eventually the U.S. and South America. Under my father’s leadership, the estate flourished in the latter half of the 20th century.

If it weren’t for my father we wouldn’t be in the position we are today. He was one of the leaders of modern winemaking in Italy and was instrumental in preserving the ancient native varieties of our region.

What does the estate consist of today i.e., how large, number of vineyards, total production, etc.?

The family estate is in the town of Atripalda which is located inland, east of Naples in the province of Avellino. The area is mountainous so the vineyards are at relatively high elevations. We have 12 different estates for a total of about 780 acres of vineyards. They all are positioned in the best areas of Campania and all are at high elevations.

We focus on the traditional varieties of Campania - Aglianico, Falanghina, Greco, Fiano, Piedirosso and Coda di Volpe. Fiano di Avellino, Greco di Tufo and Taurasi are all DOCG’s.

We focus on the traditional varieties of Campania - Aglianico, Falanghina, Greco, Fiano, Piedirosso and Coda di Volpe. Fiano di Avellino, Greco di Tufo and Taurasi are all DOCG’s.

We have total annual production of 2 million bottles. We export to about 60 countries but our main markets are the U.S., Canada, Germany, Japan, U.K. and some up-and-coming markets like Switzerland, Russia and increasingly China. These are our main markets but we have numerous sub-markets like Australia and Brazil.

If I remember correctly, the winery suffered extensive damage from an earthquake in 1980. How extensive was the damage and how did it impact your operations?

The part of our cellars that was damaged is very old, part of a larger archeological area that was the ancient town of Avellino. Since it was an important historic area the repair work had to be done very carefully because of government regulation as well as our desire to preserve this ancient area as best we could.

Our ancient family house was also extensively damaged and also had to be repaired in a very careful manner in order to protect the historic character of the structure. Both the cellars and the house underwent very careful historic restorations. Because of all the renovation we decided to also update and thoroughly modernize our winery equipment and facilities.

The earthquake also destroyed thousands of bottles of wines in our cellar. Fortunately, many bottles were spared so we still have an extensive collection of our wines dating back almost a century to the 1920’s.

Tell me a little about current management of the estate - is your father, Antonio, still involved in winery operations? Is your brother, Carlo, also involved in the winery’s operations?

My father Antonio largely retired from the business in 2005 and passed away in January of last year at the age of 86. Because of poor health my brother Carlo decided not to enter the business and so I am president with responsibility for every aspect of the business. I am the tenth generation owner-manager of the Mastroberardino family winery.

Tell me about your head winemaker - experience and number of years at winery; how do you interact with him on a day-to-day basis?

Rather than just a head winemaker, I have a six-person team of wine specialists that I work closely with. Along with my chief winemaker, Massimo di Renzo, there are two agronomists, a microbiologist, an oenology specialist and a laboratory analyst.

They are all relatively young, between 35 and 45. They all came to the winery soon after their university training and they have grown professionally with us. They basically received their training and real wine experience in our winery.

While I have extensive business contacts with universities and research groups, I have not used wine consultants nor do I anticipate doing so. I believe that a winemaker has to be intimately familiar with the local wine environment. You have to be where the vines are with your hands in the soil. You have to live there and be on call even if it’s Sunday. You can’t just live apart, then fly in and expect to contribute anything of value.

The Mastroberardino winery played a defining role in the revitalization of some of Campania’s most important varietals such as Fiano, Greco di Tufo and Aglianico. How and when did this happen and what drove these initiatives to resurrect these ancient varieties?

Many of the ancient grape varieties that had been brought to southern Italy by the ancient Greeks and subsequently cultivated by the Romans were on the verge of extinction in the 1930’s and ‘40’s. The phylloxera disease of the late 19th century had taken a toll and many winemakers after World War II were swayed by the siren calls of the “international” varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay. Many producers actually tore out their ancient rootstocks and replaced them with lower quality but higher-yielding international varieties. It was fashionable but also terrible because these producers were at risk of losing their traditions and sense of place.

Various ancient Roman writers described these ancient varietals in great detail. We have written records that describe as many as 80 different varieties and some writers developed catalogues of the various grape varieties of that era. They even differentiated between Greek and Roman varieties - Fiano and Falanghina, for example, were described as Roman varietals while others like Greco di Tufo and Aglianico were identified as having Greek origins. We have ancient Roman documents describing the wines, their structure and ageing potential, the different terroirs and even different training techniques for the vines.

My family’s interest in preserving these indigenous varietals dates back to the 1920’s but it was my father Antonio that took a leading role in the preservation of these ancient varieties. He assumed charge of the winery’s operations at the end of World War II when his father passed away. He was only 18 years old and still in high school at that time.

You can’t imagine how challenging this was for a young man. At that time the area’s vineyards were in disarray as a result of damage from the war, economic recession and just simple neglect. Everyone was negative - the markets were down and nobody wanted to produce or buy wine. He worked very hard to encourage people to grow grapes, especially the traditional varieties, and sell wines.

He began buying some prime vineyard properties for the estate while also undertaking research to identify the best vineyard sites in the area so the indigenous grape varieties could achieve their greatest potential. To preserve the ancient varieties he took the few cuttings that were left and propagated them, planting new selections in the best areas.

Antonio was one of the great pioneers of Italian winemaking, a hero of the wine business. Thanks to his research and hard work, many native Campanian varieties were saved from extinction.

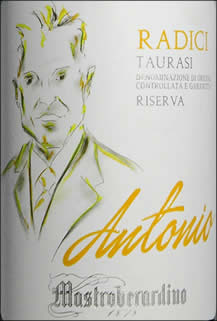

While your winery produces a number of quality white wines it is your red Taurasi Radici wines that have established your winery’s reputation. Would you agree with that assessment?

Yes, the Taurasi Radici is our flagship wine. It really has made a difference. Our 2006 Taurasi Radici Riserva was included in Wine Spectator’s top 100 wines for 2013 and has received the most awards of all our wines.

But I also think our whites are very good. In the whites we have Fiano di Avellino Radici which is one of the wines we will taste tonight (note - to be served following his presentation at the Smithsonian Resident Association conference). “Radici” translates as “roots” and we use it for our best wines to indicate our commitment to safeguarding our traditional varieties. The Fiano has impressive aromas and good character and unlike most other white wines it is very long-lived and will age well for a number of years.

What is it about Aglianico from the Taurasi zone that makes it so special or differentiates it from other Aglianico wines from Campania such as Aglianico del Taburno, Irpinia Aglianico and Sannio Aglianico?

First of all, the difference between Taurasi and other Aglianico wines from Campania is the elevation of the vineyards. The Sannio and other Aglianico areas are at much lower elevations. The Taurasi vineyards are the highest in the area. To give you some idea, there is a ski run not far from our property.

The micro-environment or terroir is also very different. The volcanic soil of the Taurasi zone is rich in minerals with good clay-loam content. There is a natural drainage system because of both the slope and clay content of the soil. The result is rich but elegant wines with concentrated flavors. Taurasi is the only red-wine DOCG zone in Campania.

I know several wine enthusiasts in the U.S. that have extensive collections of my wines that go back to the 1960’s but I have a complete inventory of my Taurasi wines going back to 1928 - that’s almost 100 years! When I talk about 100 years of the same wines, I mean I have 100 years of the same wines from the exact same vineyards.

I recently had a vertical tasting in New York City of my Taurasi wines, some of which went back 6 decades, and they were still very, very fresh. Each wine was not only drinkable but a real pleasure to drink, balanced and elegant with silky tannins. It was an event not just for me but for the world of wine.

In what ways is Taurasi Aglianico similar or different from the Aglianico del Vulture wines produced in the neighboring Basilicata region?

The main difference comes from the biotypes. The Aglianico clones are different and the terroirs in which they grow are different. Taurasi wines have a rounder and more elegant character while wines from Monte del Vulture are more full-bodied and robust compared with the Taurasi. The difference is primarily a matter of elegance and balance.

Your Taurasi Radici Riserva is the estate’s most important and valued wine. Tell me what it is about the wine that makes it so special?

First produced in 1986, the Taurasi Radici Riserva is made entirely of Aglianico grapes harvested from our Montemarano vineyard, the highest part of our estate. The vineyard is about 600 meters (almost 2,000 feet) above sea level and is right in the middle of a mountain.

The grapes are picked in mid-November and undergo a period of maceration of 25 days in a temperature-controlled environment, a strategic part of the process. The Riserva is aged in a combination of new and used oak for about 30 months, 60 percent in medium-size Slavonian oak barrels and 40 percent in barriques. The wine spends a relatively long period in the bottle, up to 42 months, before release for sale.

The wine has a full and complex spectrum of wonderful aro mas and flavors. I can stay there with a glass for hours. I feel a very emotional attachment to this wine.

mas and flavors. I can stay there with a glass for hours. I feel a very emotional attachment to this wine.

We are just now starting to release the 2008 vintage of the Riserva. It is a special Riserva that is dedicated to my father who passed away last year. I love to paint and sketch and so I made a pencil and chalk portrait of my father which appears on the ’08 Riserva label.

What non-Mastroberardino wines might I find in your personal cellar?

I love to experiment so I have wines from everywhere, oftentimes given by friends, producers or wine lovers. So I really have a good number of wines to choose from. They don’t stay around too long as I like to serve them during family luncheons or dinners or when entertaining friends.

Currently I have a good representation from around the world, both old and new. I have some Italian wines from various regions of the country. I also have some French wines with a preference for Burgundy as well as red and whites from many other regions of the world.

I really don’t have any special regional or country preferences for wines other than my own - I just love to travel with my taste.

Your winery was appointed by the Italian government to analyze and reintroduce vine growing in the ancient city of Pompeii as it was prior to the eruption 2,000 years ago. When and how did this come about?

We know that wine played an important economic and cultural role in ancient Pompeii. There are some very colorful frescoes in Pompeii today that depict how wine was used and enjoyed in those ancient times. We know that there were numerous vineyards and cellars in and around Pompeii and that wine played an important role in the culture of Pompeii. Pompeii was a prosperous port and trading center city that derived some significant part of its wealth from the sale and export of wines.

Analyzing how wine was produced and enjoyed in this ancient culture was actually a dream of my father back in the 1970’s. But it wasn’t until the early 1990’s when we started a collaborative project with the Superintendent of Antiquities that we could actually begin research on the project. Basically what we wanted to do was analyze the ancient grape varieties, the vine growing and wine-making practices of the day and produce experimental wines using traces of Pompeii's old grape varieties. This was part of a broader research effort by the Superintendent of Antiquities to make this ancient city come alive

How did you go about researching the ancient vine growing and wine-making practices?

With the assistance of various research centers in Italy and abroad we were able to identify the types of grapes grown in Pompeii from casts of vine roots that had been preserved by the ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The same technique used to locate the position of bodies in the volcanic ash was also utilized to examine the position and density of the vines in the vineyards. We examined the distance between vines and between rows and were able to precisely match our plantings with the position of the ancient vines.

In addition to the technical research we also consulted ancient sources. For example, some of the colorful frescoes unearthed in Pompeii present ancient grape leaves in great detail. The vines were very professionally rendered and we were able to identify some of the grape varieties based on these frescoes.

We also examined ancient texts. Writers such as Pliny the Elder in his multi-volume Historia Naturalis not only presented insights into the role of wine in ancient Roman culture but also some very detailed observations on ancient viticultural practices such as various methods for training vines. Pliny not only listed the numerous wines of his era but also presented a ranking of the best Roman wines. He also observed that the quality of wines will vary from location to location and that some special vineyard regions produce wines of exceptional quality, all of which predates our modern concept of terroir.

After several years of study, we were able to plant a small vineyard with eight different ancient red and white grape varieties. As our research expanded we were able to identify several other vineyard sites, one of which was close to Pompeii’s ancient amphitheater on the edge of town. In every case, we planted grape vines in the exact same locations and with the same density as the ancient vineyards. Today we have 15 separate vineyard plots

After several years of study, we were able to plant a small vineyard with eight different ancient red and white grape varieties. As our research expanded we were able to identify several other vineyard sites, one of which was close to Pompeii’s ancient amphitheater on the edge of town. In every case, we planted grape vines in the exact same locations and with the same density as the ancient vineyards. Today we have 15 separate vineyard plots

However, as we expanded our vineyard plantings we found that two red varieties, Piedirosso and Sciascinoso, proved to be the most successful in Pompeii.

As part of this project you also recreated the type of wine ancient Pompeiians were drinking prior to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD79. Can you tell me a little about the wine - how it’s made; taste; cost; availability?

In addition to researching ancient grape varieties and planting vineyards at Pompeii, the Italian government asked us to produce wine based on ancient viticulture and winemaking techniques. We very precisely followed the ancient Roman cultivation and wine-making methods described by Pliny. Interestingly, we found that their fermentation process was based on the principle of temperature control not that different from today.

What we ended up with is a blended red wine with 90 percent Piedirosso and 10 percent Sciascinoso, the two varieties that we found adapted best to Pompeii’s soils.

The wine is called Villa dei Misteri, or "Villa of the Mysteries," and is named after one of Pompeii's most famous restored sites. Some of the villa's colorful frescoes are reproduced on the label. The wine has a special IGT Pompeii classification.

But it’s not exactly the same wine that the ancient Romans drank because if it was served up today would likely be undrinkable given today’s refined standards. The ancient wines were rough stuff that were flavored with honey, spices and other condiments to preserve the wine and then had to be diluted with water to make them drinkable.

Out of necessity we used contemporary winemaking techniques. So the wine is not exactly the same as what the ancient Romans drank but rather an accurate but modern version of the old one.

The first wine to be released from Pompeii’s ancient vineyards was the 2001 vintage. We started the harvest in late October. After fermentation the wine was aged for twelve months in barriques and spent 6 additional months in bottles prior to release. The wine has a bright ruby red color and its aromas are full, complex, and persistent with intense red berry and spice flavors. It has good weight and is full, balanced and structured with prominent tannins.

Only 1,700 bottles of this first vintage of Villa dei Misteri were produced. Six bottles were presented to the President of Italy and the rest were auctioned off in Rome with the proceeds used to help further the work in Pompeii. Subsequent releases were also in limited quantities and they have become something of a collector’s item. They are difficult to find and expensive, typically selling for over $100 a bottle when you can find it.

If you don’t mind, tell me something about your personal life. Do you have any hobbies? How do you like to spend your free time?

I don’t really have a lot of free time. I spend a lot of time traveling internationally on business so I use what free time I have to rejuvenate myself and it’s mainly dedicated to artistic endeavors.

I like to write poetry. Last year I published a collection of poems and am in process of publishing another poetry volume. It will be a collaborative effort with a visual artist who will provide the artwork and I will present my poetry.

I also paint and have recently had exhibitions of my art in various cities in Italy as well as a major exhibition in Brazil last year

I am also a professor of economics at the University of Foggia where I teach and do research on management and social sciences.

What is your favorite place to visit in Italy?

Italy is so nice and the various regions are so different that each has its own charm. I like to ski and so I like to visit the ski areas in the north of Italy. It is a beautiful area of Italy.

I love the country and like to travel the countryside on my motorbike. I recently toured the Amalfi coast on my motorbike and that was really excellent - it’s without a doubt the best way to see the Amalfi coast.

What about the next generation of the Mastroberardino family?

I have two girls - 14 and 12 years of age. I brought my older daughter to New York last year because she wanted to attend a memorial dinner dedicated to my father.

So the eleventh generation of owner-manager of the Mastroberardino estate may well be two females, a first for the family. But they are young, and who knows, they may well have their own agenda.

Well, I think that wraps it up. Thank you for taking the time to meet with me and congratulations on your work at Pompeii.

Thank you. It has been my pleasure.

©Richard Marcis

June 2, 2015

Return to About Italian Wines

Help keep this website ad-free and independent.

Consider making a contribution to support the work of WineWordsWisdom.com.